Dr. Justin Rhinehart

Professor and Extension Beef Cattle Specialist

Department of Animal Science

P: 931-486-2129

Co-Author: Courtnie Carter; Beef Program Coordinator, UT Animal Science

One of the most important aspects of Extension work is conducting field demonstrations. Dr. Seaman Knapp – considered the father of Extension – summed that up perfectly with this quote found in a biography written by O.B. Martin.

More than 100 years ago Knapp said, “There is a vast difference between the knowledge of a thing and that knowledge which enable us to practically make use of the thing.” Later in this same book goes on to ask, “Is it not true that the easy thing for us to do is learn general principles and theories, and the difficult part is to apply them?”

The answer to Dr. Knapp’s question is yes, it is easier to learn the general principles than it is to implement them. So, he went the extra mile to work with hundreds of farmers in hundreds of communities on implementing new technologies, recording the results, and then using those results to demonstrate to other farmers in those communities what could be done by adopting those methods themselves. His approach continues to be effective for improving farm productivity in local communities and, by telling those farmers’ stories on a broader scale, across the country more than a century later.

The purpose of this article is to tell the story of an ongoing field demonstration here in Tennessee that shows the importance of proper reproductive management for improving the profitability of beef cattle production. In the spring of 2019, we began working with a young commercial cow/calf producer who was taking over management of her family’s herd after graduating from college. The cattle operation is one part of a larger diversified farm enterprise and management of the herd had taken a back seat to the other parts of their business.

Seeing It

Our first step was to evaluate each cow in the herd so we could establish short- and long-term objectives and then develop a plan to reach those objectives. This evaluation included assigning a body condition score, mouthing to estimate age, evaluating structural soundness (eyes, udders, and mobility), and assigning a disposition score. Another extremely important step was to determine pregnancy status since bulls had remained with the cows year-round. Records were not available to make culling decisions based on historical weaning weights or calving intervals.

The initial evaluation was used to make obvious culling decisions and then decide on the most ideal calving season. A plan was put in place to improve the overall reproductive management by moving toward a single calving season in the fall (September – October). In this demonstration, an aggressive culling approach was used to achieve a greater year-to-year difference and “clean up” the cow herd and condense the calving season as quickly as possible. So, 56 of the initial 200 cows were sold after the evaluation based on when they were expected to calve, structural soundness, and disposition. The bulls were removed in late summer.

In the winter of 2019, estrus synchronization for natural service was used to condense the breeding season beyond what was achieved by the initial culling. The main goal of using synchronization for natural service was to stimulate cows to conceive quickly after the start of the breeding season and reduce the overall calving season length. Timed artificial insemination was also used to breed a group of replacement heifers that were purchased as non-pregnant yearlings along with a few home-raised heifers that were retained. A group of 47 pregnant cows was also purchased to increase herd size. All cows and heifers we pregnancy checked by ultrasound after the breeding season. Nonpregnant females and those expected to calve

The following winter of 2020, estrus synchronization for natural service was again used on mature cows by inserting a controlled intervaginal drug releasing (CIDR) device for seven days and introducing bulls when it was removed. Two-year-old cows (i.e., first-calf heifers) and virgin heifers were bred by timed artificial insemination. By this point, a mobile working facility had been purchased making it easier to work cows and apply these types of technology for all breeding groups.

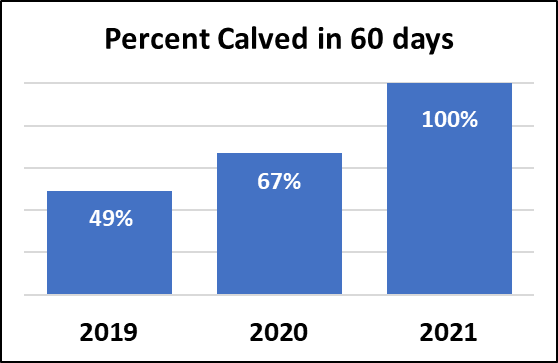

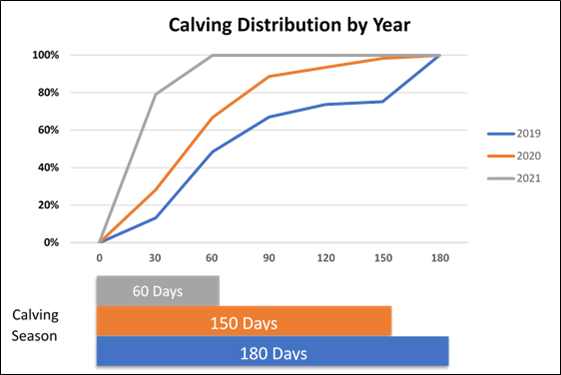

The dramatic impact of making these management decisions can be seen in Figure 1 that shows the percent of cows calving (2019 and 2020), or due to calve at the time of writing of this article (2021), in the first 60 days of the calving season. In other words, a sixty-day calving season was achieved with an initial deep culling and two subsequent breeding seasons. Another important outcome beyond quickly achieving a defined calving season is the distribution of calving within those two months (Figure 2).

Believing It

Condensing the calving season has made it easier for this producer to manage nutrition and health, two factors that had been neglected prior to her taking over management. The average BCS of her cows has gone from 4 (the low end of BCS 4) to a solid 5 (almost 6) while her winter feed bill has gone down dramatically. All that while wintering lactating cows. Aside from the pinkeye issues most everyone faced this year, the need to treat cows for health issues has also decreased dramatically. Having a more uniform set of calves has provided her with the opportunity to market in larger groups and manage price risk which, with the additional weight from marketing more total calves that are heavier and older at weaning, has increased total revenue produced per cow.

If you ask Ragan McFall if she thinks “the juice is worth the squeeze?” she is quick to tell you that she is enjoying the lemonade. The best part – it will be easier for her to maintain or improve these results in the years to come as she layers on more profit potential from improved genetics and adding other technologies. We will provide updates on Ragan’s progress and stories from other demonstrations across the state in future article so you can see it, believe it, and do it yourself.

Figure 1: Percent of cows calved (2019 and 2020) or due to calve (2021) in the first sixty days of the calving season.

Figure 2: Calving distribution and calving season length as the result of reproductive management decisions.